Explanatory Feedback: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

*<p style="font-size:13px">Sweller, J. (2010). Element Interactivity and Intrinsic, Extraneous, and Germane Cognitive Load. Educ Psychol Rev 22, 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9128-5</p> | *<p style="font-size:13px">Sweller, J. (2010). Element Interactivity and Intrinsic, Extraneous, and Germane Cognitive Load. Educ Psychol Rev 22, 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9128-5</p> | ||

=='''References'''== | |||

Clark, J. M., & Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory and education. Educational Psychology Review, 3(3), 149–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01320076 | |||

Mayer, R. E., & Sims, V. K. (1994). For whom is a picture worth a thousand words? extensions of a dual-coding theory of multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(3), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.86.3.389 | |||

Sweller, J., van Merrienboer, J. J., & Paas, F. G. (1998). Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design. Educational Psychology Review, 10(3), 251–296. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022193728205 | |||

Wong, K. M., & Samudra, P. G. (2019). L2 vocabulary learning from educational media: Extending dual-coding theory to dual-language learners. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(8), 1182–1204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1666150 | |||

<div style="text-align: center;">'''Return to [[https://ectwiki.online/index.php?title=Main_Page Main Page]] | [[#top|[Top Page]]] '''</div> | <div style="text-align: center;">'''Return to [[https://ectwiki.online/index.php?title=Main_Page Main Page]] | [[#top|[Top Page]]] '''</div> | ||

Revision as of 17:39, 17 November 2022

Overview

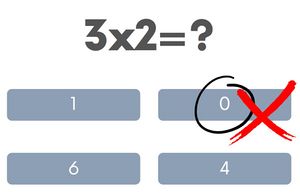

Explanatory feedback provides learners with an explanation of whether their answers are correct, which can help learners avoid misunderstanding and help establish a correct mental model (Clark & Mayer, 2011) to achieve more effective learning outcomes. It is an essential concept in the feedback principle proposed by Richard E. Mayer[1] and Logan Fiorella. They believe that novice students learn better when they have explanatory feedback than when they are given corrective feedback[2] alone (Mayer & Fiorella, 2021).

Evidence

Roxana Moreno[3] (2004) recruited 49 college students to conduct an experiment demonstrating explanatory feedback's favorable impact on learning. He randomly assigned these students to two groups, one group provided explanatory feedback (EF group), and the other group provided corrective feedback (CF group). All the students took the prior knowledge test to ensure they were novices, and they will learn how to design plants through a multimedia learning program later. During the learning process, students in the EF group will receive verbal explanations from a software pedagogic agent, informing students whether their choices are correct and explaining why they are correct or wrong (Moreno, 2004). The students in the CF group will only be informed whether their options are correct by the software pedagogic agent(Moreno, 2004). Afterward, Roxana conducted a multivariate analysis on these students to compare the differences in their learning outcomes. Results show that when the agent provides explanatory feedback alongside corrective feedback during the knowledge construction process, students have higher retention and transfer levels and more positive ratings of the difficulty and usefulness of the instructional program than students who have corrective feedback alone (Moreno, 2004).

Design Implications

We can often see the role of explanatory feedback in online school exams. For example, in a calculus exam, the grader only pointed out the wrong answer without providing any explanation, which is a form of corrective feedback. This grading method made all students very confused and didn't know how to understand the questions they did wrong, and it also prevented them from learning from their mistakes. After students reported this problem to the grader, in addition to pointing out students' mistakes in the subsequent exams, the grader will also add his comments next to his marks, which is a form of explanatory feedback. After changing his grading strategy, all students who took the exam can self-reflect when faced with their own mistakes and think about the correct problem-solving method according to the grader's explanation. It also greatly improves the effectiveness and efficiency of students' learning. Students no longer need to spend extra time searching for relevant information, and they can also avoid going on the wrong path due to their misunderstanding of concepts.

Related: Cognitive Load Theory

Richard E. Mayer and Logan Fiorella also mentioned in their article that the delivery method of feedback may bring extraneous cognitive load to learners, thus affecting explanatory feedback's effectiveness (Clark & Mayer, 2011). The extraneous cognitive load refers to the cognitive load brought to students due to inappropriate instructional procedures (Sweller, 2010). According to Cognitive Load Theory[4], learners' working memory capacity is limited, and cognitive load refers to the number of working memory resources used(Sweller, 2010). When learners' working memory is overloaded, students will not be able to process new knowledge, and explanatory feedback will become less effective.

References

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2011, January 20). E-learning and the science of instruction. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=MOutGGET2VwC&lpg=PA238&ots=XNqiCizZCn&dq=explanatory+feedback&pg=PA239#v=onepage&q&f=false

Mayer, R., & Fiorella, L. (Eds.). (2021). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (3rd ed., Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108894333. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-handbook-of-multimedia-learning/09E09224829AB8D3D327EF8A0E9B5288

Moreno, Roxana. (2004). Decreasing Cognitive Load for Novice Students: Effects of Explanatory versus Corrective Feedback in Discovery-Based Multimedia. Instructional Science. 32. 99-113. 10.1023/B:TRUC.0000021811.66966.1d. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:TRUC.0000021811.66966.1d

Sweller, J. (2010). Element Interactivity and Intrinsic, Extraneous, and Germane Cognitive Load. Educ Psychol Rev 22, 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9128-5

References

Clark, J. M., & Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory and education. Educational Psychology Review, 3(3), 149–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01320076 Mayer, R. E., & Sims, V. K. (1994). For whom is a picture worth a thousand words? extensions of a dual-coding theory of multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(3), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.86.3.389 Sweller, J., van Merrienboer, J. J., & Paas, F. G. (1998). Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design. Educational Psychology Review, 10(3), 251–296. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022193728205 Wong, K. M., & Samudra, P. G. (2019). L2 vocabulary learning from educational media: Extending dual-coding theory to dual-language learners. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(8), 1182–1204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1666150