Flow: Difference between revisions

Tanvivartak (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Tanvivartak (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

== '''Example''' == | == '''Example''' == | ||

In | In a state of flow, a student working towards practice problems for an upcoming test may lost track of time. Moreover, they are fully engaged in the task at hand (practising for the test), given they are sufficiently challenged. The student also derives a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction as they progress through the problems <ref> Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row. </ref> | ||

== '''Evidence''' == | |||

In a 2011 study by Cheng and colleagues <ref> Cheng, Y., Chen, C., & Liu, Y. (2011). Flow experience and learning outcomes of university students: An empirical study. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 20(1), 19-26. doi: 10.1007/s40299-011-0002-2 </ref> examined the relationship between flow and learning in an educational context. The researchers found that students who experienced a state of flow during a learning activity performed better on a subsequent test of the material than students who did not experience flow. This suggests that flow may enhance learning by improving focus and engagement and by promoting a sense of mastery and achievement. | |||

Flow has also been studied in the context of language learning <ref> Kim, J., Park, H. W., & Lee, J. H. (2017). The relationship between flow experience and foreign language learning: A study of Korean university students. Asia Pacific Education Review, 18(1), 27-36. doi: 10.1007/s12564-016-9463-8 </ref> . The study found that learners who experienced flow during a language learning activity demonstrated greater gains in language proficiency than learners who did not experience flow. This suggests that flow may enhance learning by promoting deep engagement with the material and fostering a sense of ownership over the learning process. | |||

Lastly, individuals who experienced flow during a design thinking task demonstrated greater creativity and problem-solving ability than individuals who did not experience flow. This suggests that flow may enhance learning by promoting a sense of autonomy and creativity, which can lead to deeper understanding and more innovative solutions <ref> Shin, D. H., Kim, H. J., & Kim, H. W. (2018). The effect of flow experience on creativity in a design thinking context. Journal of Creative Behavior, 52(4), 389-401. doi: 10.1002/jocb.212 </ref>. | |||

== '''Critique''' == | == '''Critique''' == | ||

Revision as of 16:31, 23 February 2023

Overview

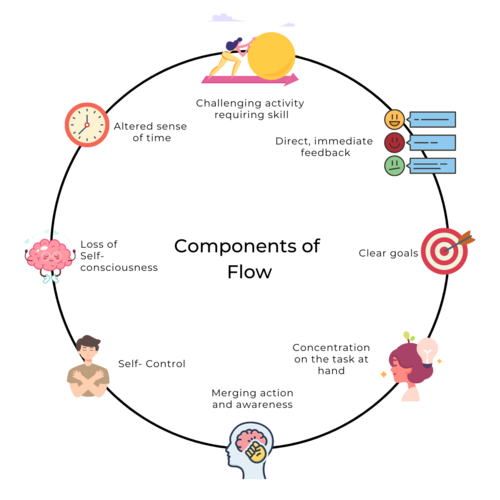

The concept of flow is defined as a mental state of complete absorption in an activity leaving the individuals performing the task feeling energised and focused while enjoying the task at hand. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi [1] introduced the “flow zone”, the context in which the state of flow is experienced. Mihaly attributed the eight flow components - while all may not be necessary to achieve the flow state.

Example

In a state of flow, a student working towards practice problems for an upcoming test may lost track of time. Moreover, they are fully engaged in the task at hand (practising for the test), given they are sufficiently challenged. The student also derives a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction as they progress through the problems [2]

Evidence

In a 2011 study by Cheng and colleagues [3] examined the relationship between flow and learning in an educational context. The researchers found that students who experienced a state of flow during a learning activity performed better on a subsequent test of the material than students who did not experience flow. This suggests that flow may enhance learning by improving focus and engagement and by promoting a sense of mastery and achievement.

Flow has also been studied in the context of language learning [4] . The study found that learners who experienced flow during a language learning activity demonstrated greater gains in language proficiency than learners who did not experience flow. This suggests that flow may enhance learning by promoting deep engagement with the material and fostering a sense of ownership over the learning process.

Lastly, individuals who experienced flow during a design thinking task demonstrated greater creativity and problem-solving ability than individuals who did not experience flow. This suggests that flow may enhance learning by promoting a sense of autonomy and creativity, which can lead to deeper understanding and more innovative solutions [5].

Critique

However, metacognitive processes can also be unhelpful, especially when individuals hold an illusion of knowing [6]. Thus, they may not spend enough time recalibrating themselves to the appropriate knowledge. Secondly, the task performance would get affected by overshadowing, that is, the negative verbalization of cognitive tasks. Thirdly, metacognitive judgments or feelings reflecting a negative self-evaluation would detract individuals from engaging in the process of learning [7]. Lastly, altering the course of existing procedural knowledge is challenging as it is often automatic.

Conclusion

Metacognitive abilities significantly enhance and improve individuals' awareness while learning [8]. Hence, learning designers need to ensure the integration of metacognition without adding strain or overshadowing, instead supporting individuals in self-reflecting to be better learners. One way is to align metacognitive strategies with learning tasks, especially for procedural and conditional knowledge [9]. Additionally, identifying strategies that students need to select and how to use them, especially given differences in how individuals can enact the same learning strategies. Next, it would be necessary to understand the standards of self-evaluation individuals hold during metacognitive processing and ideate solutions, especially for students who do not want to confront what they don’t know. Finally, it is vital to leverage the effect of ability, motivation, and skill on metacognition while integrating it into learning design

References

- ↑ Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

- ↑ Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

- ↑ Cheng, Y., Chen, C., & Liu, Y. (2011). Flow experience and learning outcomes of university students: An empirical study. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 20(1), 19-26. doi: 10.1007/s40299-011-0002-2

- ↑ Kim, J., Park, H. W., & Lee, J. H. (2017). The relationship between flow experience and foreign language learning: A study of Korean university students. Asia Pacific Education Review, 18(1), 27-36. doi: 10.1007/s12564-016-9463-8

- ↑ Shin, D. H., Kim, H. J., & Kim, H. W. (2018). The effect of flow experience on creativity in a design thinking context. Journal of Creative Behavior, 52(4), 389-401. doi: 10.1002/jocb.212

- ↑ Epstein, W., Glenberg, A. M., & Bradley, M. M. (1985). Coactivation and comprehension: Contribution of text variables to the illusion of knowing. Memory & Cognition, 12(4), 355–360. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03198295

- ↑ Norman, E. (2020). Why metacognition is not always helpful? Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01537

- ↑ Welter, V. D. E., Becker, L. B., & Großschedl, J. (2022, May 5). Helping Learners Become Their Own Teachers: The Beneficial Impact of Trained Concept-Mapping-Strategy Use on Metacognitive Regulation in Learning. Education Sciences, 12(5), 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050325

- ↑ Stanton, J., Sebesta, A., & Dunlosky, J. (2021). Fostering metacognition to support student learning and performance. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.20-12-0289)