Cognitive dissonance theory

Overview

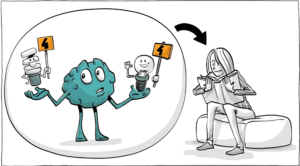

In cognitive dissonance theory, people seek consistency between what they believe and what they do. According to the theory, people strive for consistency between what they believe and what they do [2]. When there is an imbalance between the two, tension is created. Cognitive dissonance can be reduced by changing either beliefs or behaviors so that they become mutually consistent and harmonious. There are times when people change their behavior to match their beliefs; this is often seen as an ethical imperative since we should practice what we preach [2].

The first investigator of Cognitive Dissonance is Leon Festinger. According to Leon Festinger, after observing a cult that believed the earth would be destroyed by a flood, a series of cognitive dissonance that occurred following the flood did not occur since different members of the cult behaved differently before the “phony disaster” which led to radically different outcomes following the “crisis of doom”. To avoid dissonance, or disharmony, we strive to maintain harmony between our attitudes and behaviors, as explained by Festinger's cognitive dissonance theory[3].

Evidence

There are three causes of Cognitive Dissonance: Forced Compliance Behavior, Decision Making, and Effort. Force Compliance Behavior happens when individuals are forced to comply with actions that are inconsistent with their beliefs. Due to the fact that the behavior was already in the past, dissonance will need to be reduced by reevaluating their attitudes. And this cause of cognitive dissonance had been tested experimentally by Festinger and Carlsmith (1959)[4]. In their laboratory experiment, they used 71 male students as participants to perform a series of dull tasks (such as turning pegs in a peg board for an hour), and get paid either $1 or $20. It was found that those who received only $1 rated the tedious task as more enjoyable and fun than those who received $20 to lie. The $1 payment was not sufficient incentive for those who lied, so they experienced dissonance. In order to overcome that dissonance, they had to believe that the tasks were interesting and enjoyable[4]. Due to the fact that they receive $20 for turning pegs, there is no dissonance. As a result that dull task would create cognitive dissonance through forced compliance behavior.

Decision Making is decision-making as a general rule creates dissonance. It was Brehm[5] who first studied how dissonance affects decision-making. The study participants were promised a product in return for their participation as part of a compensation package funded by several manufacturers. In the second step, the women rated eight household products ranging in price from $15 to $30 according to their desirability. The products included automatic coffee makers, electric sandwich grills, automatic toasters, and portable radios. One of the products was given to participants in the control group. Participants didn't need to reduce dissonance since they didn't make a decision. On an 8-point scale, low-dissonance group members chose between a desirable product, and one rated 3 points lower. Those who participated in the high-dissonance test had to choose between a highly desirable and a less desirable product. The products were rated again once individuals read the reports about them. Participants in the high-dissonance condition increased the attractiveness of the chosen alternative more than those in the other two conditions and decreased the attractiveness of the alternative they didn't choose. Therefore, cognitive dissonance also happens when there is decision-making.

The Effort represents the situation when a person spends years of effort achieving something but does not receive something back equally, in order to prevent dissonance from occurring, the person would try to convince themselves that they didn't really spend years of effort, or that it was really quite enjoyable, or that it wasn't really that much of an effort[6]. We could, of course, spend years of effort into achieving something which turns out to be a load of rubbish and then, in order to avoid the dissonance that produces, try to convince ourselves that we didn't really spend years of effort, or that the effort was really quite enjoyable, or that it wasn't really a lot of effort. An experiment on dissonance was carried out by Aronson and Mills in 1959[6]. In the experiment, a group of female students volunteered to take part in a discussion on the psychology of sex and read aloud to a male experimenter a list of sex-related words in different levels of embarrassment conditions. After the experiment, the result showed that participants in the “severe embarrassment” condition gave the most positive rating. The result showed that dissonance happened when a bad outcome with a lot of effort, so redefining the experience is interesting and helps reduce the dissonance.

Design Implications

Challenges and/or Alternative theories

Taking a critical stance regarding the cognitive dissonance theory,

References

- ↑ Sprout. (2022, October 20). Cognitive dissonance: Our battle with conflicting beliefs. YouTube. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GxAu7BTZQRY

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Martinez, M. E. (2010). Learning and cognition: The design of the mind. Perusalk (Vol. 6). Merrill. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://app.perusall.com/courses/foundations-of-cognitive-science-for-learning-f22/learning-and-cognition-the-design-of-the-mind?assignmentId=ZKHADfR8srroXsmKM&part=1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 McLeod, S. (1970, January 1). [cognitive dissonance]. Study Guides for Psychology Students - Simply Psychology. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-dissonance.html

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58(2), 203.

- ↑ Brehm, J. W. (1956). Postdecision changes in the desirability of alternatives. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52(3), 384.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59(2), 177.