Learning emotions

Overview[edit | edit source]

Emotions[edit | edit source]

Emotions are defined as multifaceted phenomena [1] involving sets of coordinated psychological processes, including affective, cognitive, physiological, motivational, and expressive components [2].

Loderer et al [3] explain emotions as a person’s reactions to internal and external events and describe its components as:

- Affective components - subjective feelings (for example, positive appreciation connected to gratitude)

- Cognitive components - consisting of emotion-specific thoughts (e.g. confidence in one’s ability to solve a current problem)

- Physiological components - supporting associated action (e.g. physiological activation for sadness)

- Motivational components - encompassing behavioral tendencies (e.g: tendencies to disengage during boredom)

- Expressive components - facial, postural, and vocal expression (e.g. speaking in a soft voice) [4]

Learning Emotions[edit | edit source]

Emotions are crucial to learning because long-term memory stores factual and emotional associations to prior knowledge.[5] Moreover, emotions experienced in the educational settings are instrumental in academic achievement and personal growth.

For example, a student might experience enjoyment while working on a challenging task. Thus promoting creativity, achievement of goals, flexible problem-solving, and supports in self-regulation [6]. Conversely, a student may also experience excessive anxiety while learning particular subjects thereby impeding their academic performance and ability. This may also have a detrimental effect on their psychological and physical health. [7]

Types of learning emotions[edit | edit source]

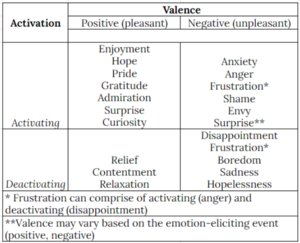

According to Russell [8], the two most important dimensions to emotions for explaining variance in human affect are valence (pleasant/ positive, unpleasant/ negative) and activation (activating, deactivating).

Dimensions of emotions[edit | edit source]

In terms of valence, positive (i.e., pleasant) states, such as enjoyment and happiness, can be differentiated from negative (i.e., unpleasant) states, such as anger, anxiety, or boredom. With respect to activation, physiologically activating states differ from deactivating states, such as activating excitement versus deactivating relaxation. [9].

Important learning emotions[edit | edit source]

According to Loderer et al (2020) [10], the following groups of emotions are important with respect to learning:

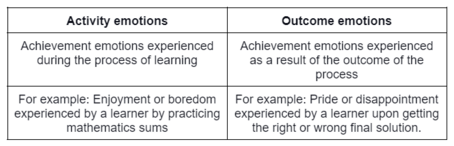

- Achievement emotions Pekrun et al [11] define achievement emotions as “emotions that relate to activities or outcomes that are judged according to competence-related standards of quality.” Achievement emotions can be further classified as:Outcome emotions can include prospective emotions such as anxiety or hope regarding future activities or retrospective emotions, like guilt, pride, or shame relating to a past achievement.

- Epistemic emotionsEmotions can be caused by cognitive qualities and the processing of task information. [12] A typical sequence of epistemic emotions induced by a cognitive problem may involve (1) surprise, (2) curiosity and situational interest if the surprise is not dissolved, (3) anxiety in case of severe incongruity and information that deeply disturbs existing cognitive schemas, (4) enjoyment and delight experienced when recombining information such that the problem gets solved, or (5) frustration when this seems not to be possible. [13]

- Social emotionsEmotions experienced concerning others or in social contexts are called social emotions. Social interactions tend to influence the interactions and engagement of the learner and the other members of their environment. For example, the feelings of envy or awe of others for their achievements.

- Topic emotionsEmotions elicited by the contents covered by the material to be learned are called topic emotions. For example, experiencing anxiety while studying mathematics or joy while playing a science simulation.

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Emotions can influence cognitive processes and learn [14] [15] They strengthen initial learning by yielding the power of focusing attention. Moreover, learners can recall strong emotional experiences later in time. [16]

The role of emotions in learning can assume two hypotheses:

- Emotions as suppressors of learning

- Emotions as facilitators of learning

Emotions as suppressors of learning[edit | edit source]

This hypothesis postulates that emotions impair information processing by taking away attention from information to be learned. [17] For example, if a learner has emotions that affect their perception of the task, it places additional demand on the working memory while learning. This interferes with the processing of essential information. [18]

Emotions as facilitators of learning[edit | edit source]

Knörzer et al [19] posit that emotions as a facilitator-of-learning hypothesis assume that emotion fosters information processing. Studies [20] have suggested that positive emotions have a positive impact on information processing. Moreover, emotions also expand the scope of attention while learning [21]. Um, et al. [22] argued that emotion facilitates working memory processes, e.g. memory encoding. Positive emotions also facilitate retrieving information from long-term memory by serving as a cue [23]. This also results in better learning taking place in a positive state of mind [24]. Learners are also able to form associations with their prior knowledge with the help of positive emotions, thereby contributing to meaningful learning as a result of deeper understanding.

Implications to learning design[edit | edit source]

Emotional design becomes important in learning design [25] as it directs the learner's attention toward essential learning material and motivates them to learn deeper. For example, a student may experience positive emotions like empathy in a classroom where the teacher extends kindness toward their learner. Thus the learner tends to learn in a relaxed atmosphere fostered by the teacher. This also improves their perception of the subject matter and the teacher. The student may also experience enjoyment as an activity emotion. Furthermore, this would also increase the learner's engagement in the process and improves the outcome of their performance.

With respect to multimedia design, Um, et al [26] study established that students learning material that aimed to foster positive emotional multimedia design generated higher positive emotions and learned better as tested in retention and transfer tests. Supporting this, Mayer and Estrella [27], concluded that students who learned material with a positive emotional learning design performed better than students from the controlled group. Heidig, et al [28] also concluded that the learner’s emotional states affected their intrinsic learning motivation.

Challenges[edit | edit source]

While research has focused on emotional design and learning, there is very little research that currently exists in order to understand the emotions the learner experienced during the process of learning.[29] Moreover theories like the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning does not consider the impact of emotion in learning that may affect the cognitive load to exceed the cognitive capacity of the learner’s working memory. Furthermore, given differences between individuals and cultures, there are varying intensities, expressive behavior and internal experiences that students undergo during the process of learning which need to be further investigated and validated.

Metacognition and emotions are remains as one area of crucial study, since metacognition is an effective strategy for generative processing. Understanding the role of emotions in this process would help in designing tools that would account into factors of emotional design while developing metacognitive tools for learning.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Shuman, V., & Scherer, K. (2014). Concepts and structures of emotions. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 13–35). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis

- ↑ Kleinginna, P. R., & Kleinginna, A. M. (1981). A categorized list of emotion definitions, with suggestions for a consensual definition. Motivation and Emotion, 5, 345–379

- ↑ Loderer, K., Pekrun, R., & Plass, J. (2020). Emotional foundations of game-based learning [Print]. In Handbook of Game-based Learning (pp. 113–114). The MIT Press.

- ↑ Shuman, V., & Scherer, K. R. (2014). Concepts and structures of emotions. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 13–35). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- ↑ Bower, G. H., & Forgas, J. P. (2001). Mood and social memory. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Handbook of affect and social cognition (pp. 95–120). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- ↑ Clore, G. L., & Huntsinger, J. R. (2009). How the object of affect guides its impact. Emotion Review, 1, 39–54

- ↑ Zeidner, M. (1998) . Test anxiety: The state of the art. New York, NY: Plenum.

- ↑ Russell, J. A. (1978). Evidence of convergent validity on the dimensions of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(10), 1152–1168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.10.1152

- ↑ Shuman, V., & Scherer, K. (2014). Concepts and structures of emotions. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 13–35). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ Loderer, K., Pekrun, R., & Plass, J. (2020). Emotional foundations of game-based learning [Print]. In Handbook of Game-based Learning (pp. 113–114). The MIT Press.

- ↑ Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). Introduction to emotions in education. In International Handbook of Emotions in Education. Taylor & Francis Group.

- ↑ Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). Introduction to emotions in education. In International Handbook of Emotions in Education. Taylor & Francis Group.

- ↑ D’Mello, S. K., & Graesser, A. C. (2014). Confusion. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 289–310). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006- 9029-9.

- ↑ Yang, H., Yang, S., & Isen, A. M. (2013). Positive affect improves working memory: Implications for controlled cognitive processing. Cognition & Emotion, 27(3), 474–482.

- ↑ Bower, G. (1994). Some relations between emotions and memory. In The nature of emotions: Fundamental questions. Oxford University Press

- ↑ Uzun, A. M., & Yıldırım, Z. (2018). Exploring the effect of using different levels of emotional design features in multimedia science learning. Computers & Education, 119, 112–128.

- ↑ Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. New York: Springer.

- ↑ Knörzer, L., Brünken, R., & Park, B. (2016). Emotions and multimedia learning: The moderating role of learner characteristics. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32(6), 618–631.

- ↑ Erez, A., & Isen, A. M. (2002). The influence of positive affect on the components of expectancy motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1055–1067 https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1055.

- ↑ Chung, S., Cheon, J., & Lee, K. W. (2015). Emotion and multimedia learning: An investigation of the effects of valence and arousal on different modalities in an instructional animation. Instructional Science, 43(5), 545–559.

- ↑ Um, E., Plass, J. L., Hayward, E. O., & Homer, B. D. (2012). Emotional design in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 485–498.

- ↑ Isen, A.M., Thomas, E.S., Clark, M., & Karp, L. (1978). Affect, accessibility of material in memory, and behavior: A cognitive loop? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,36(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.36.1.1

- ↑ Rader, N., & Hughes, E. (2005). The influence of affective state on the performance of a block design task in 6- and 7-year-old children. Cognition & Emotion, 19(1), 143–150 https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000049.

- ↑ Mayer, R. E., & Estrella, G. (2014). Benefits of emotional design in multimedia instruction. Learning & Instruction, 33(33), 12–18 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.02.004.

- ↑ Um, E., Plass, J. L., Hayward, E. O., & Homer, B. D. (2012). Emotional design in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 485–498.

- ↑ Mayer, R. E., & Estrella, G. (2014). Benefits of emotional design in multimedia instruction. Learning & Instruction, 33(33), 12–18 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.02.004.

- ↑ Heidig, S., Müller, J., & Reichelt, M. (2015). Emotional design in multimedia learning: Differentiation on relevant design features and their effects on emotions and learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 44(44), 81–95 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb. 2014.11.009.

- ↑ Li, J., Luo, C., Zhang, Q., & Shadiev, R. (2020). Can emotional design really evoke emotion in multimedia learning? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00198-y